An ad tweeted by Old Navy in 2016 sparked some online outrage and the use of the hashtag #BoycottOldNavy. What was it that stirred people's ire? The clothing company had shown a cheery interracial family clad in Old Navy garb. Some accused the company of being “anti-white” and “promoting race-mixing.” Others praised the company’s inclusiveness and even shared photos of their own interracial families with the competing hashtag #LoveWins.

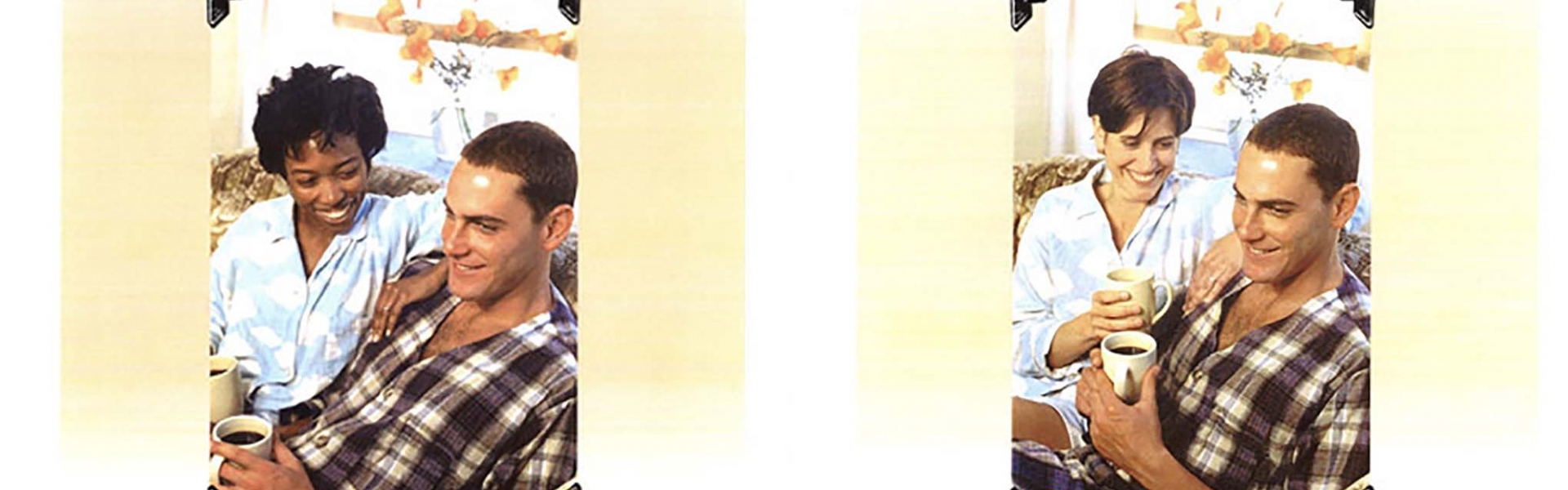

These divided reactions, in part, led SF State Professor of Marketing Subodh Bhat to question whether ads showing mixed-race couples elicited greater negative reactions than ads depicting same-race couples.

Bhat’s study, published in the March 2018 issue of the Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, found that ads depicting black and white couples elicited more negative emotions and attitudes toward the brand than comparable ads showing same-race couples.

“A lot of the research that’s been done around this subject has been done in sociology and social psychology, but not in the business field,” Bhat said. “Because of my interest in controversies in advertising, I was curious what I would find.”

The study’s finding was somewhat surprising, given that the 2010 U.S. census found that 15 percent of all new marriages were interracial, up from 7 percent in 1980, Bhat said.

Bhat’s study included 291 students at a major southern public university, most of whom were under 25 years old. Fifty-nine percent were male and 41 percent were female, while 60 percent were white and 40 percent were black. The survey included 24 questions and four random ads featuring couples of the same race and mixed race. Overall, the results suggested that ads showing mixed-race couples raised negative emotions and lowered individual opinions of the brand.

Another surprising finding, according to Bhat: there was no difference between the attitudes of white and black respondents or between men and women in their views on mixed-race couples. “Generally, literature has suggested blacks are more accepting of white-black relationships than whites and females were more accepting than males,” he adds. “In this research, it did not seem like there was any difference across race and gender.”

Bhat suggests there could be a slight variance in perception of ads showing interracial couples based on regional differences. “We might have a more muted reaction, but the basic reaction still holds,” he said. “This is not just based on my research but on a lot of other research I’ve seen.”

Marketers tend to steer clear of campaigns that generate a lot of controversies because they have a bottom line to consider and it’s in their best interest to court a wide audience, Bhat said. Companies that want to promote diversity and inclusivity should approach the matter thoughtfully, he advises, perhaps by showing ads with different kinds of couples.

“Ikea did this a number of years ago with ads showing different kinds of couples, including older couples or disabled couples — something you don’t often see in ads,” he said. “Courting controversy by itself is not very meaningful. If you’re trying to be seen as inclusive and socially responsible then you should use an interracial couple as one of the different kinds of couples you show.”