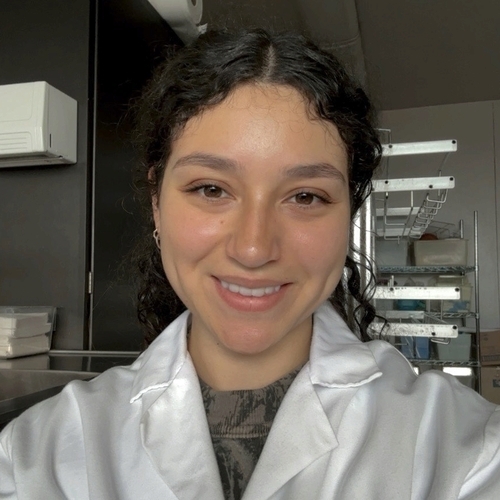

Rising star: University researcher Berenice Baca achieves firsts in sea star research

With faculty support, a scholarship award-winning student expands class project into a graduate research project

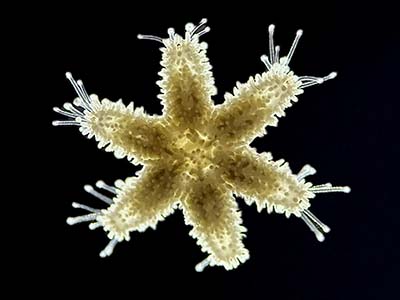

It’s not often that one gets to throw starfish a birthday party. Some species — like the six-rayed sea star Leptasterias — are notoriously difficult to keep alive in the lab, making even first birthdays a rarity. So when San Francisco State University researcher Berenice Baca achieved the seemingly impossible feat of raising Leptasterias specimens for an entire year, her lab made sure to celebrate.

Baca is among the first in her field to successfully rear Leptasterias embryos to reach the one-year milestone in the lab. And to think, this project started in an undergraduate class with San Francisco State Biology Professor Sarah Cohen.

“Because of that study I started as an undergrad, I was able to grow [Leptasterias] up to a year, which is really exciting,” said Baca, who joined Cohen’s lab as an undergraduate researcher and is now an SF State master’s student. She’s been with this project for less than two years but she’s already shared her work at national and international conferences, won research awards, attended research workshops and worked with KQED to highlight these sea stars.

Baca’s work could help Leptasterias and other species feeling the impact of grave challenges. Sea stars face the constant threats of climate change and sea star wasting disease, a mysterious condition wiping out entire species. “We tend to notice or shift our attention towards certain species when it’s endangered or almost gone,” Baca explained. “We should try to address [these issues] now rather than wait until the species is almost completely gone.”

Berenice Baca

Happy birthday, dear Leptasterias…

Baca studies the developmental patterns of two species of Leptasterias sea stars (Leptasterias pusilla and Leptasterias aequalis). These species reproduce via brood-fostering, which is akin to a hen sitting on her eggs. While somewhat common among other animals, it’s a rare approach among marine species. In the wild, maternal sea stars protect 50 – 1,500 embryos on their underside until their young stars are ready to be independent. Baca successfully raised these embryos to a juvenile stage in the lab without maternal care (i.e., without brooding). As part of this project, she developed protocols for this process and gleaned unique insight about Leptasterias development.

“As I was starting this project, I realized there’s no information on this, which drove me a little crazy,” Baca said, noting that the knowledge gap fueled her curiosity and determination.

Her first step was to give the sea stars a laboratory home as cold as their native habitat. Baca first raised the stars at 9 to 10 degrees Celsius in a classroom cold room before moving them to a dedicated deli fridge set at 12 to 13 degrees Celsius. Next, she needed to ensure that the stars didn’t starve. This was quite the saga, Baca explains, because the stars kept losing interest in readily available fish food. It turned out Baca’s microscopic juvenile starfish — approximately 0.2 cm in size — required live sea snails, copepods and barnacles they could hunt.

“I ended up getting these microscopic snails that required really fine tweezers to get them out of barnacles. I was doing this at 5 in the morning or very late at night because I have to correlate [my work] with the tides,” she explained.

Juvenile Leptasterias less than 2 cm in size.

Sea star next to a finger for scale.

Sea star hunting a sea snail.

Comparable studies on Leptasterias failed to grow the early juveniles in the lab and only one known study was able to hatch these stars. Extending Leptasterias’ lifespan in the lab gave Baca the opportunity to document their development as early as eight hours to 31 days, allowing her to capture beautiful images of fertilized eggs and snapshots of intermediate stages. By day 44, her juvenile stars began taking on a familiar six-armed star shape, and by 10 months the stars were 1.3 cm or bigger and started exhibiting hallmark coloration and patterns. Sharing her work at conferences, she was heartened to hear other scientists share excitement for her work and give her words of encouragement.

Baca and the Cohen lab even worked with KQED to feature Leptasterias in a new episode of its science video series “Deep Look,” presented by PBS Digital Studios. Scroll to the end of this story to see the video, which has nearly a quarter-million views on YouTube.

Growing up alongside her stars

Coming to SF State, Baca knew she wanted to do research, but she’s still a bit awestruck by how her research experience has evolved. When she enrolled in Cohen’s “BIOL 586GW: Marine Ecology Laboratory — GWAR,” Baca wanted research experience, but she didn’t anticipate it would lead her to pursue a master’s degree.

“It’s really nice that Sarah [Cohen] is really good at figuring out your interest and connecting you with the right people,” Baca said, explaining that Cohen encouraged her to apply for grants and scholarships, participate in conferences and attend science workshops.

Baca’s honors included the Achievement Reward for College Scientists (ARCS), Step to College and University scholarships. “That really helps. Sometimes you feel lost and having that [support] really helps in initiating your own project or research. It actually makes you feel like a scientist.”

With daily lab work, field research and conferences, being a scientist has become a big part of her life. Baca, a first-generation student, previously maintained multiple jobs and worked full-time in the fields picking blueberries and grapes to support her University education. Growing up in a small town that lacked proper science education, she had an unsatisfied desire to learn more. It’s that natural and unwavering curiosity that’s driven her throughout her research, especially when it gets hard.

“I’m really thankful for the entire Cohen lab,” Baca said, adding that Cohen’s and her lab mates’ support and encouragement have been instrumental. “I believe without them I wouldn’t have anything.”

For more information about donating to the College of Science & Engineering, contact

Holly Fincke at hollyfincke@sfsu.edu

Tags